Swiss Regional Nature Parks Promote Biodiversity Conservation Agri-Environment Schemes

Foto: Gabriela Brändle,

Agroscope

Designation of regional nature parks in Switzerland significantly boosts the adoption of direct payment schemes aimed at promoting biodiversity conservation (agri-environment schemes, AES), particularly in regions with relatively more intensive farming and low prior uptake of such schemes.

Although both regional nature parks and agri-environment schemes (AES) aim to conserve biodiversity, the interaction between these two policy instruments is unknown. A recent study investigated the effects of designating a region in Switzerland as a regional nature park on the uptake of biodiversity conservation AES within the region.

Two policy instruments with one common objective: to promote biodiversity

Since 1993, agri-environment schemes (AES) focused on biodiversity have been a major policy instrument in Switzerland for integrating biodiversity conservation into agriculture. Farmers receive direct payments for fulfilling the requirements of the AES. There are currently three types of biodiversity conservation AES in Switzerland: action-based (Q1), result-based (Q2), and agglomeration payment schemes.

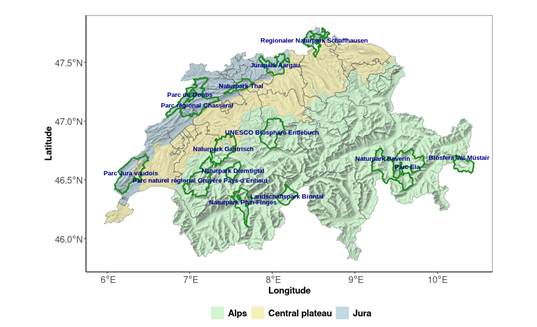

Regional nature parks are one type of large-scale, less stringent protected area supported by environmental policy. They do not restrict economic activities such as agriculture, but rather aim to integrate nature and biodiversity conservation into sustainable land use and socioeconomic development. In Switzerland, 15 regional nature parks were established in rural areas between 2008 and 2018 (Figure 1).

The dark green lines mark park boundaries at the time of park establishment.

Both regional nature parks and biodiversity conservation AES have the objective of promoting biodiversity. Therefore, regional nature parks may influence farmers’ decisions to participate in AES. For instance, as part of their strategies to promote nature and biodiversity conservation in the region, many parks organise and coordinate projects to promote sustainable agriculture.

Researchers from Agroscope and ETH Zürich investigated the effect of regional nature parks on the uptake of AES. Using econometric methods, they analysed a combination of census data (AGIS) on the AES adoption of over 42,000 Swiss farms between 2005 and 2020 and survey data on AES-related support offered by 15 regional nature parks.

Synergies between regional nature parks and AES

The researchers found that overall, compared to non-park areas with similar natural and socioeconomic conditions, farmers in areas with regional nature parks on average increase their uptake of result-based AES (Q2) by 12% relative to the periods before parks are established. This indicates an overall synergy between parks and result-based AES, and thus between environmental and agricultural policy measures.

Synergies arise primarily in regions with more intensive agricultural production

The 15 Swiss parks span two major landscape types, the Alps and the Jura (Figure 1), which differ in agricultural production intensity and biodiversity conservation. Prior to park establishment, AES adoption was much higher in the Alps due to less intensive agriculture and richer biodiversity.

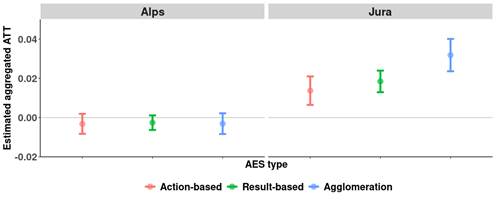

Further examining park effects on the adoption of AES over the two regions, the researchers found that the effects vary largely (Figure 2). In the Jura region with relatively more intensive agricultural production and lower pre-park AES adoption, parks on average increase the adoption of action-based (Q1), result-based (Q2) and agglomeration AES by 9.5%, 51%, and 74%, respectively. By contrast, establishing a park in the Alps has no effect on the adoption of AES.

Y-axis indicates change in share of agricultural land enrolled in AES due to park establishment. The estimated effects in percentage points translate to 9.5%, 51%, and 74% increases in the adoption of action-based, result-based, and agglomeration AES in the Jura region relative to AES adoption before park establishment.

Effects do not hinge on a particular form of support offered by the park

Using a survey among all 15 park offices, the researchers also investigated whether park effects on AES adoption vary depending on whether parks provide informational or financial support to farmers. They found no evidence that adoption is influenced by either type of support, suggesting instead that the combined set of park policies may shape farmers’ decisions on AES participation overall.

Conclusions

- Overall, regional nature parks increase farmers’ adoption of result-based biodiversity conservation AES.

- Regional nature parks are most effective in increasing biodiversity conservation AES uptake when introduced in more intensively farmed regions with low prior adoption.

- In these regions, parks likely reduce barriers to adoption and therefore create synergies with AES.

- Whether synergies between regional nature parks (an environmental policy) and biodiversity conservation AES (an agricultural policy) can arise depends on the production conditions where the new policy (park) is introduced, and the initial uptake of the existing biodiversity payment scheme.

Bibliographical reference

Protected Areas and Agricultural Biodiversity Conservation—Do Parks Increase AES Adoption?.